First conceived when she was a child (though she named it later), Atlantica was used by Bey’s father to explain Earth’s oppressive systems. Inspired by the science fiction they both loved, he told Bey that they were aliens from outer space, which gave them distance from which to observe Earth’s problems. In doing so, they created an imagined home built from resistance—and full of possibility—that was not always available in her every day.

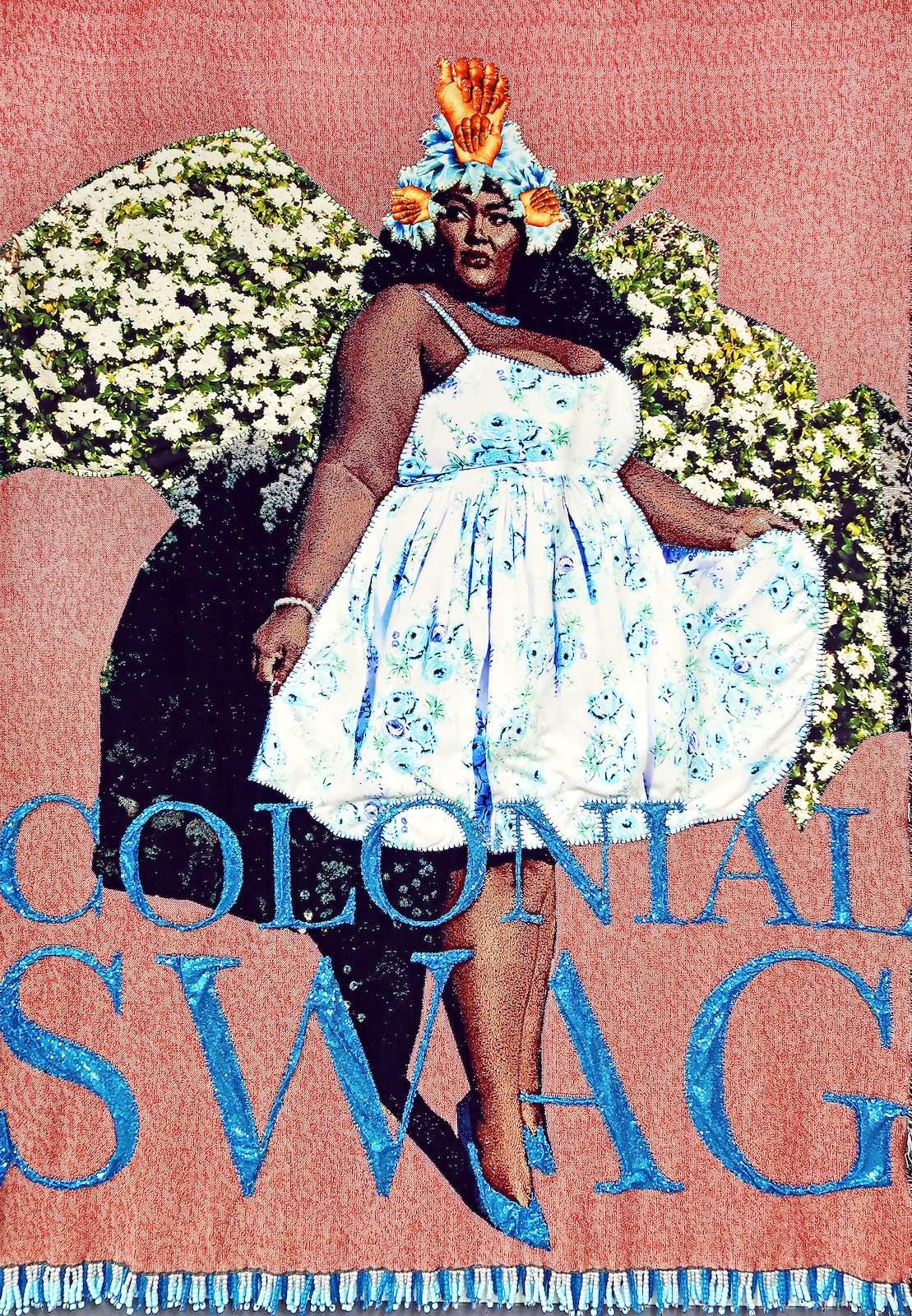

Bey spent most of her childhood in the Bahamas, a place that was vibrantly beautiful and giving, but also home to a post-colonial culture. “It’s breathtakingly beautiful everywhere. Our houses are painted Pepto Bismol pink, teal, and purple. The ocean was amazing, and growing up, we lived off of it, and what it produced,” she recalls. On the other hand, it’s “a post-colonial British country, and I grew up in the colonial school systems with corporal punishment.”

Her family ran a booze cruise and a restaurant, and she explains that growing up in the tourism industry was very traumatic. “When people go on vacation, a lot of rules that they ordinarily would follow at home go out the window. I was introduced to a lot of adult things that I should not have been introduced to. It made me dislike drinking alcohol, it made me dislike loud environments,” she says. “Also, the standard of living is a lot different for Bahamians than it is for visitors.” She points to the fact that electricity was diverted to support tourism, meaning the hotels would not experience outages, while Bahamians would go without power. Bey considers tourism a form of colonialism, and it’s something that comes up in her work—it’s also why nothing like this happens on Atlantica.