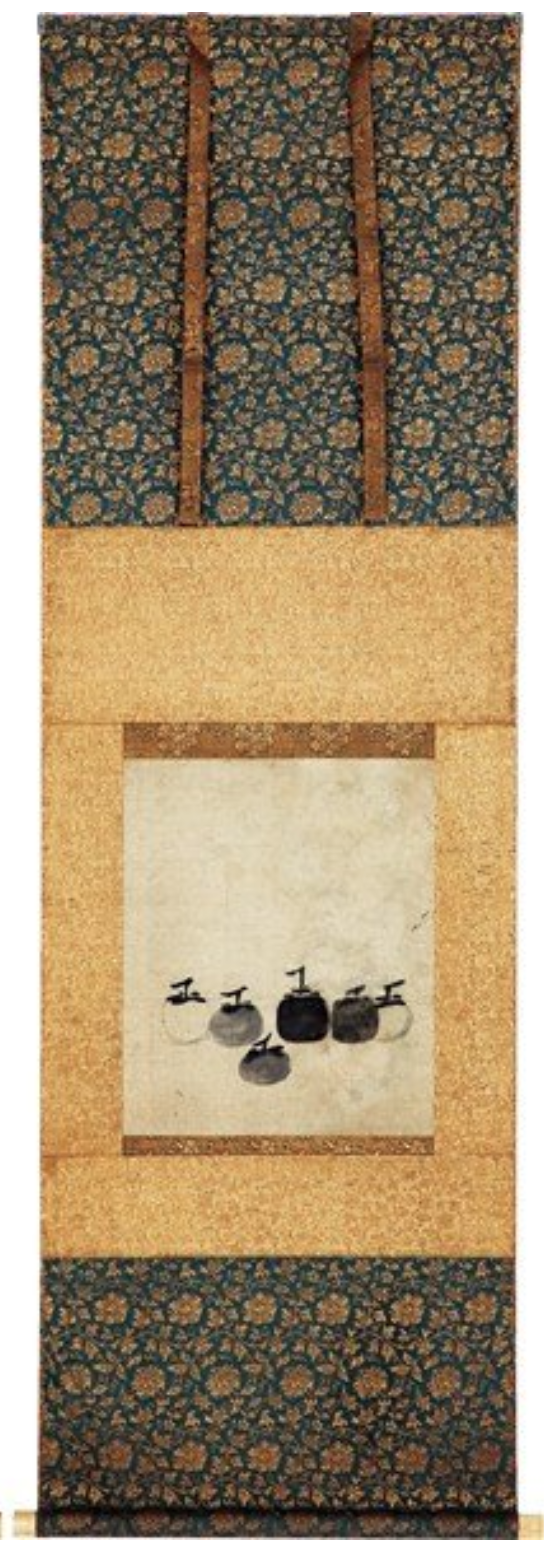

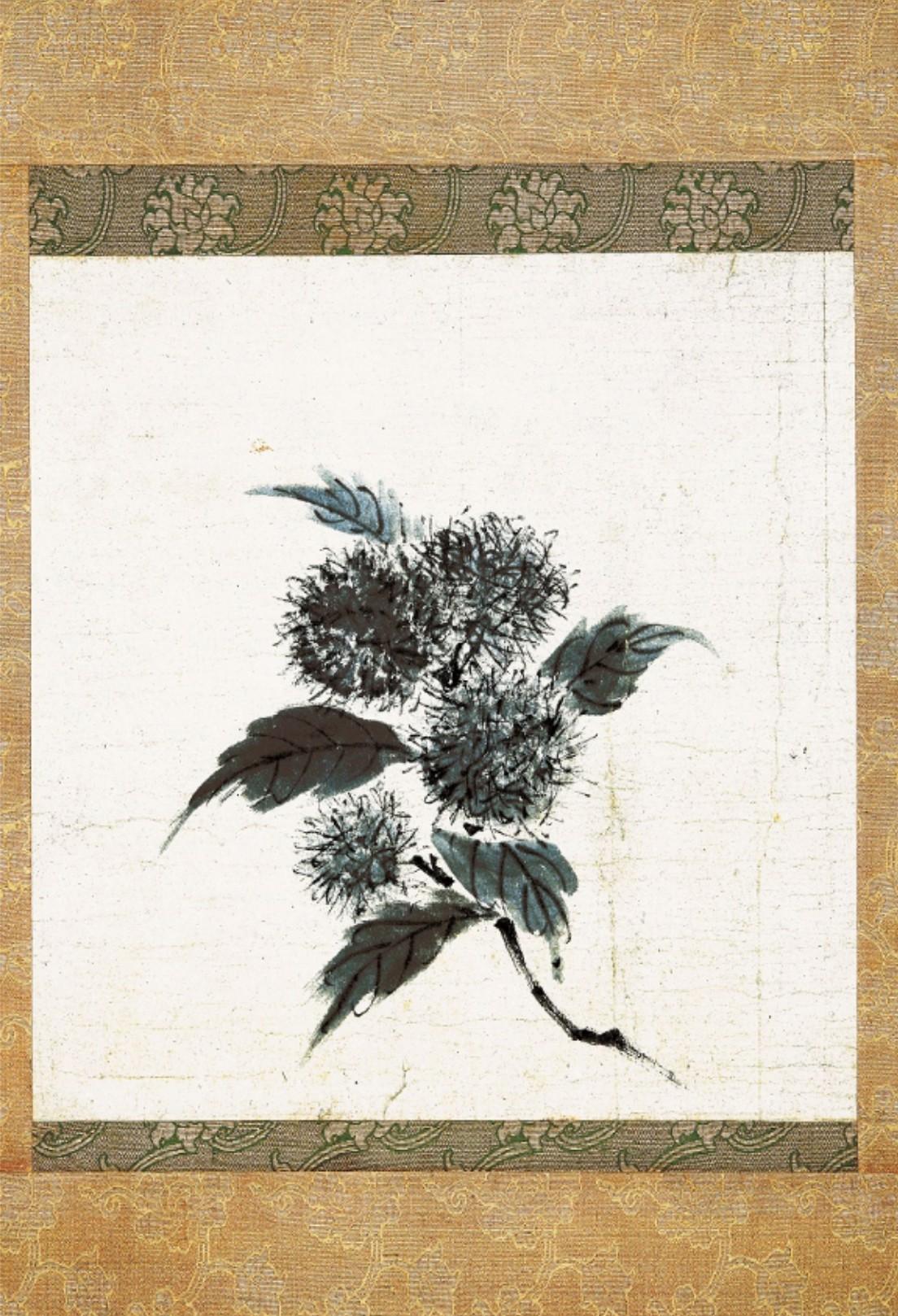

What is so special about Six Persimmons and Chestnuts? And most importantly, why are they seen as two of the finest examples of Zen art? At first glance, the two paintings are quite bare and simple. Six Persimmons portrays the six fruits in different shapes and shades of ink, with the stems pointing in various directions, and with an asymmetrical distance between them. Similarly, Chestnuts shows a branch of a chestnut tree with leaves and four chestnuts. Both paintings feature a darker, central figure flanked on both sides by other elements in lighter shades, different sizes and orientation. The darker figure draws the viewer’s gaze to the center and allows the multiple elements to be perceived as one. This stylistic choice was common among the Chinese painters who worked in the last decades of the Song Dynasty (960-1279). Yet, Muqi was different from his contemporary colleagues and it might be for this reason that his works were more appreciated in Japan than in China.

Six Persimmons and Chestnuts depict common, mundane objects in a straightforward way. The brushwork is simple, effortless but with a recognizable degree of skillfulness. In the Chinese painting environment, it was common for artists to reference previous masters through the use of brushwork “in the style of [name of the master].” Muqi did not do this and by keeping his brushwork spontaneous, he embraced the foundation of Zen art: monochrome ink painting that allows for individual expression, tranquility, and absence of perfection. The artist therefore provided an unmediated understanding of the object without the intrusion of his own personal style. Many Chinese literati and connoisseurs found themselves let down by this unorthodox choice and had little interest in the preservation of such works.