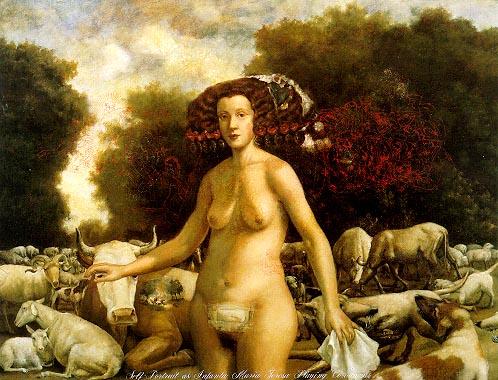

The artist first used the term “self-portrait” when she was inventing scenarios of subconscious imagery overlaid on fruit to create “a portrait of interiority.” She speaks with intimate candor about what could be considered her first proper self-portrait, driven by experiencing an ectopic pregnancy two years prior. Inspired by a Diego Velázquez portrait, in Self-Portrait as Infanta Maria Theresa Playing Coriolanus (1995), Heffernan combined her own body, complete with abdominal bandage, with the Infanta’s head. By merging with the queen, who herself had lost five of her six children, Heffernan felt a direct linkage: “I was suddenly aware of all the women in history who’d died in childbirth.”

To avoid objectification of the female nude, Heffernan gave her Infanta a direct gaze as Velázquez had done—a straightforward look that was “... always essential to position her as a woman with agency, a confrontational force,” she explained. The self-portrait then became a way of addressing her audience directly: “... presenting myself as a ... host, inviting viewers to enter the worlds I was making, [and] offering them a sense of female subjectivity ....”