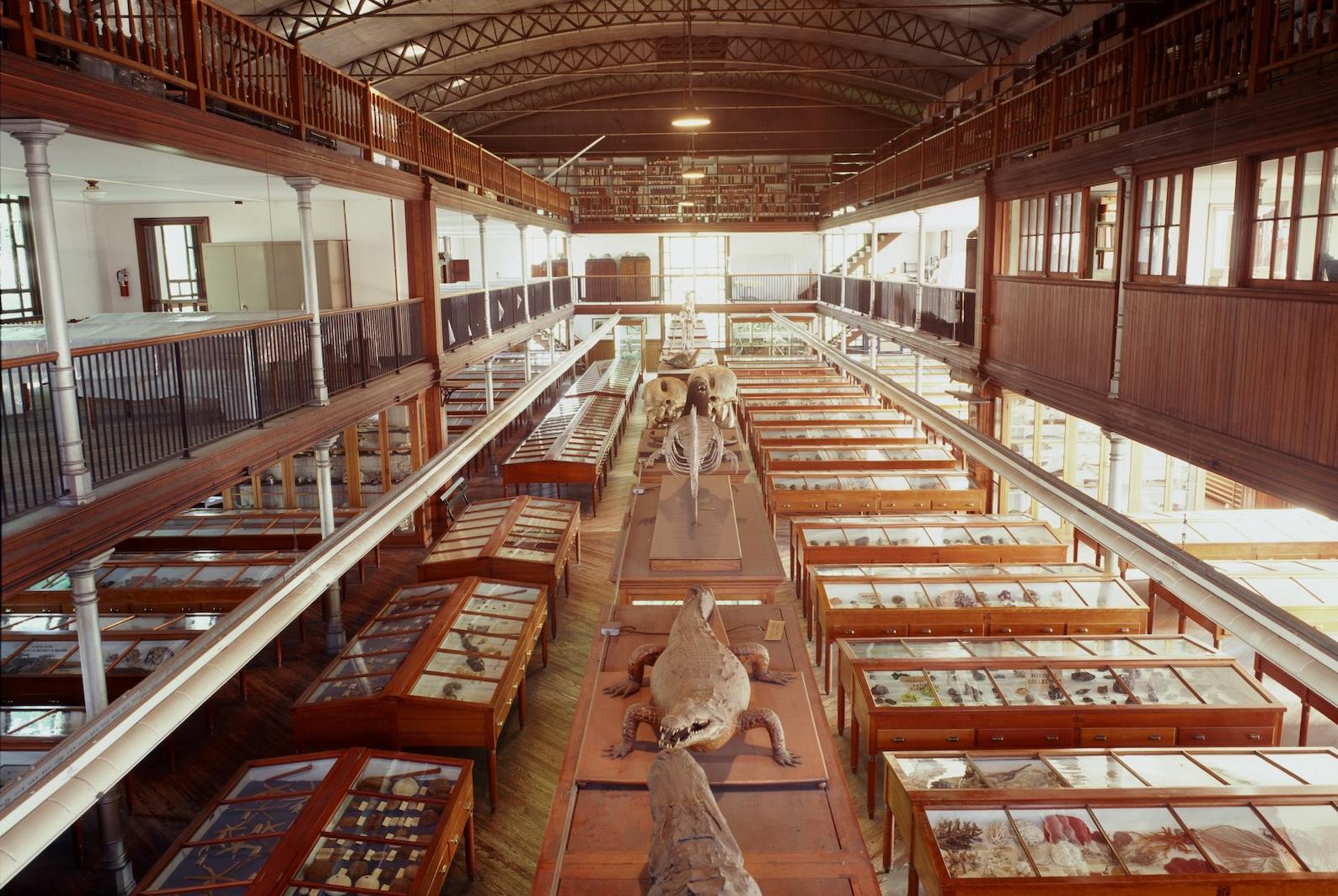

Walking into the gallery is like being transported in time—to an era where evolution was a new and controversial theory and when the unfathomable biodiversity of the world remained a mystery to most. “It’s like stepping into a different atmosphere,” says Librarian Lynn Dorwaldt, describing a first-time encounter with the Wagner’s gallery. From the gargantuan, multi-story windows that flood the gallery with light, to the antique wooden floors and cases that house more than 100,000 specimens, the gallery is a snapshot of Victorian-era science: not just in appearance, but in organization and curation.

The Wagner’s many specimens (including fossils, minerals, taxidermy, skeletons, and more) are arranged systematically, meant to showcase not only the diversity of life on Earth but methods of taxonomic categorization still used by scientists today. They are arranged from oldest—about 2.5 billion years old—to most recent. The historical context of the collection remains intact, and displays the thought process of scientists at this time, notes Dorwaldt: “an attempt to categorize and put in order everything on Earth.”

Keeping such a diverse and antique group of specimens in good condition can present unique challenges. In typical natural history museums, specimens are stored in hermetically sealed and temperature-controlled cases. Their value for scientific research is dependent on such conditions, explains Don Azuma, the site manager at the Wagner. However, in this museum, the specimens have been subject to the changing seasons for over a century, and to add temperature control now would likely do more harm than good.