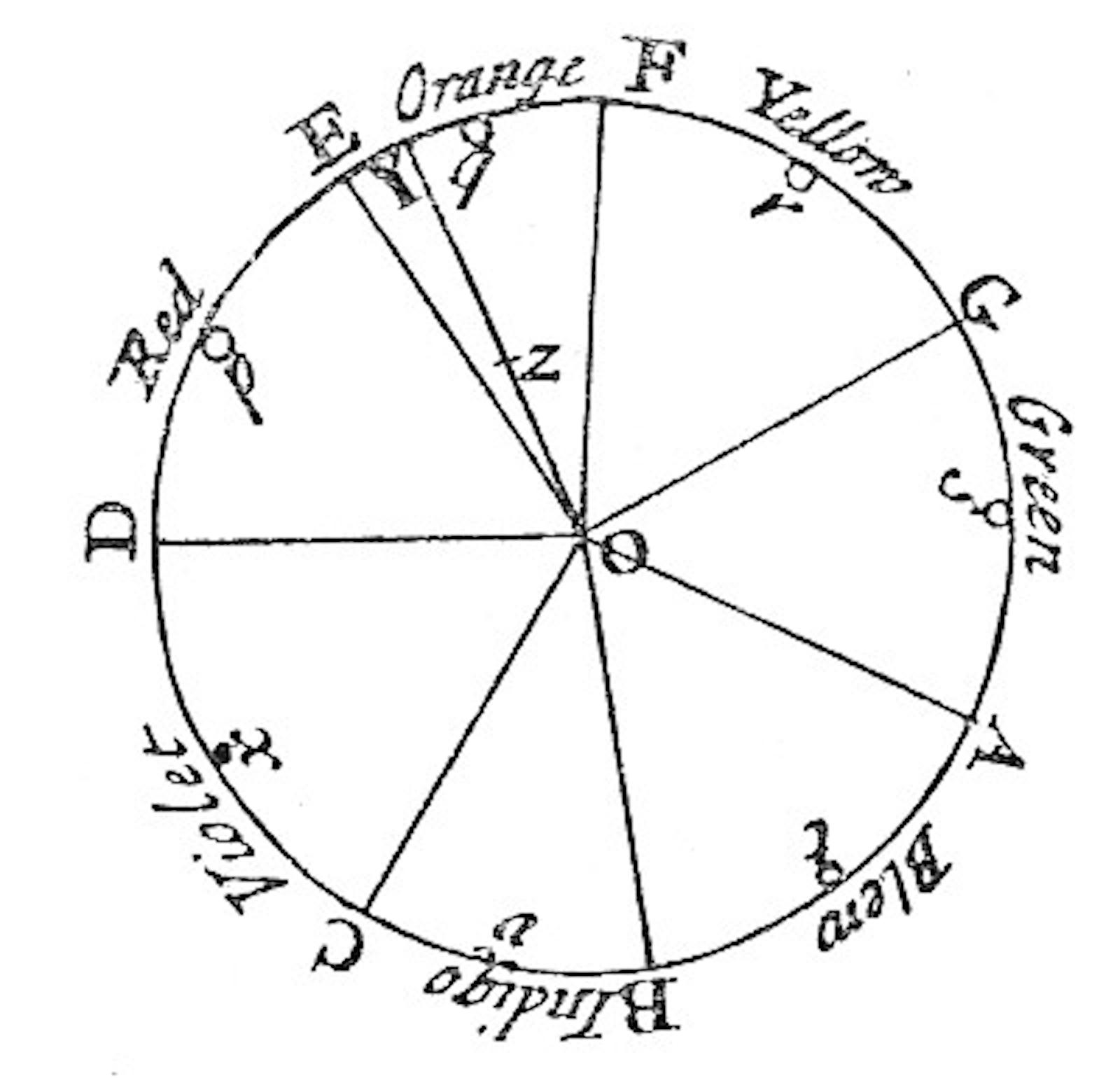

Unlike modern color wheels, it was designed to illustrate the mixture of lights, it only featured spectral hues, and it was not evenly divided. Even so, Newton made the lastingly impactful decision to arrange the colors in a circle that illustrated a connection between the violet and red ends of the light spectrum.

It’s important to note that, about a century before Opticks, Aron Sigfrid Forsius did create a circle to illustrate observed relationships between colors. This was very different from Newton’s iteration and the modern version. It graded colors on a scale between black and white and only featured red, yellow, green, blue, and grey.

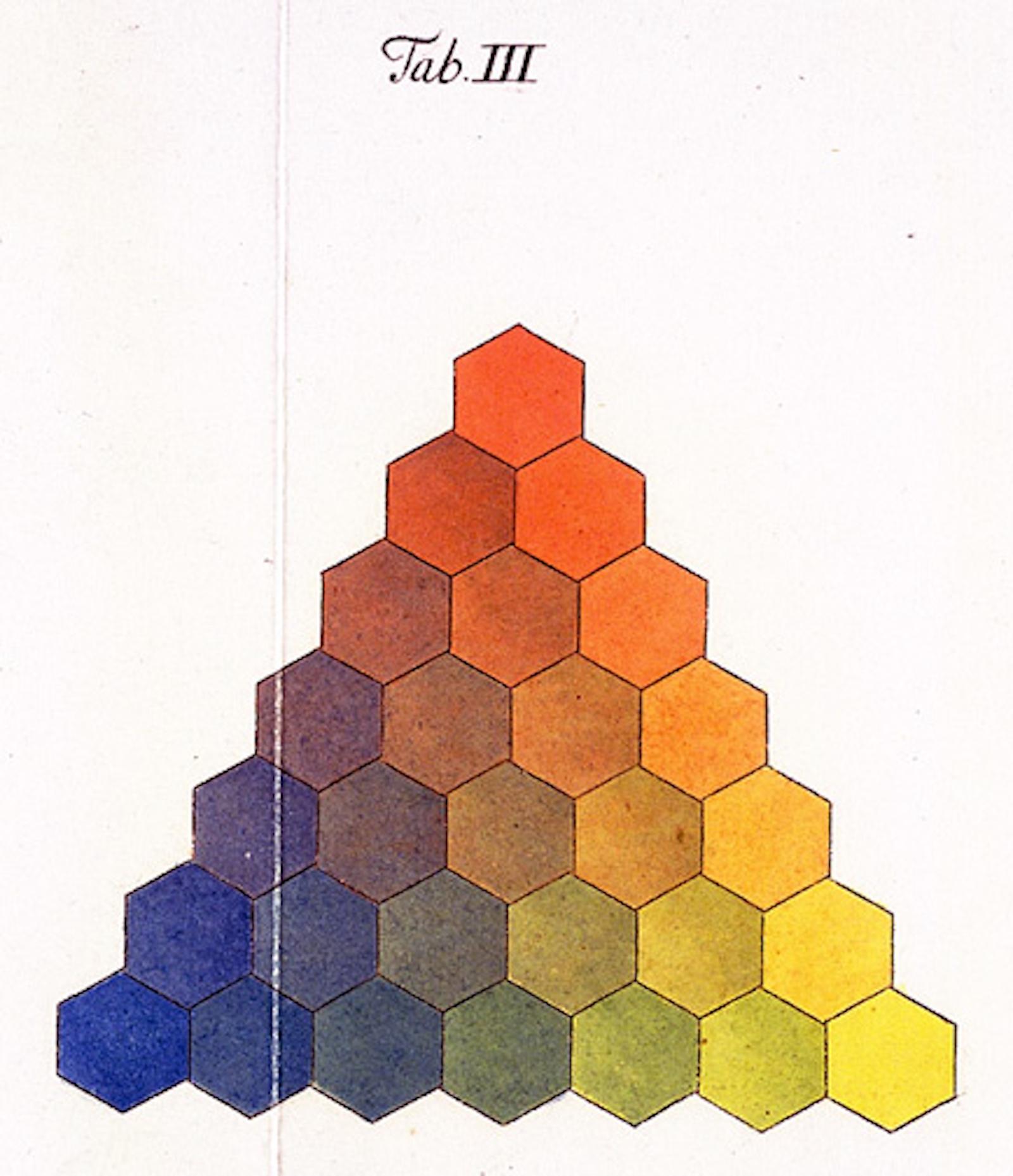

In the late eighteenth century, Tobias Mayer created a color triangle with the primary colors red, yellow, and blue at each point. Each point was connected to its adjacent points by twelve gradations of color—Mayer believed that this was the highest degree of color variation the human eye could detect. Later, a physicist by the name of Georg Christian Lichtenberg worked from Mayer’s triangle to create a new version with seven gradations per side.