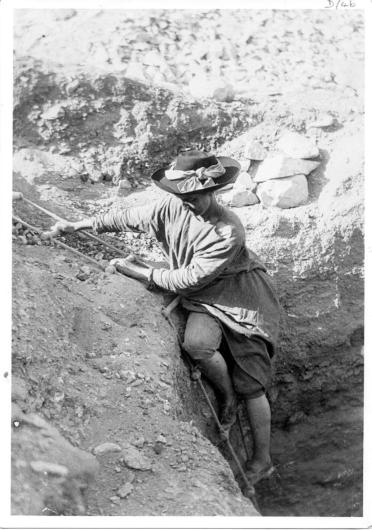

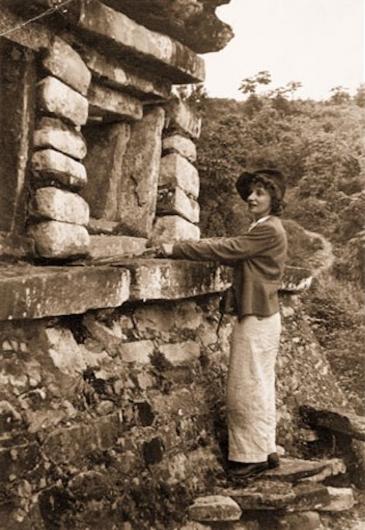

Hilda Petrie descending a ladder into an Egyptian Tomb.

Problems of gender inequity have plagued academia since its inception with women being discouraged or outright barred from learning and practicing different sciences and art forms.

Even in the field of archaeology, a discipline that aims to study the full breadth of past societies (which would have been more or less fifty percent women), women were discriminated against, and their participation in academic archaeological pursuits was severely limited. Education reforms of the late twentieth and twenty-first centuries minded towards gender equity have greatly improved women’s access to educational and professional positions in archaeology and countless other fields. However, such progress could not have been made without the foundational contributions of the women who defied the odds society set against them and carved out room for themselves in a field that was otherwise unwelcoming or even hostile. A complete list is impossible, but here are some noteworthy women in archaeology whose early contributions to the field both broadened our knowledge of the past and opened up space for future generations of women.

Hilda Petrie (1871-1957) was an Irish-born Egyptologist and geologist best known for her contributions to the study of ancient Egyptian tombs. Born in 1871, Hilda spent most of her childhood in London which granted her access to the city’s many museums and art galleries. As a young woman, she studied geology at the King’s College for Women where she displayed considerable talent, especially in the drawing of facsimiles. When she was twenty-five, the painter Henry Holiday – for whom Hilda had sat as a model years before – introduced Hilda to the Egyptologist Flinders Petrie who was in need of a skilled drawer for making accurate copies of inscriptions and artifacts. The two married not long after their introduction and began their first of many trips to conduct excavation work in Egypt.

Unlike many other wives of archaeologists who traveled with their husbands, Hilda was not expected to maintain the domestic aspects of the expedition camp but was instead a full-time, active participant in the archaeological process. Her accurate copies of hieroglyphs and artifacts were invaluable to the projects she co-conducted and eventually directed. Together with her husband, Hilda was also instrumental in establishing the British School of Archaeology in Egypt which trained countless scores of future archaeologists.

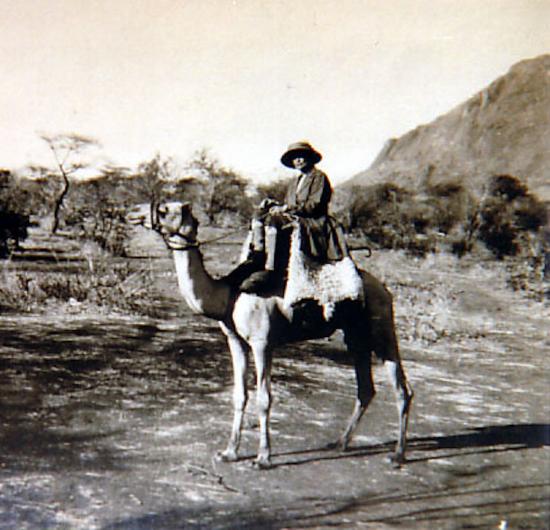

Grace Crowfoot (1879-1957) was an English-born archaeologist who helped pioneer the archaeology of fabrics and textiles. Hailing from a well-off family of the landed gentry, Grace was in contact with the ancient world from an early age, thanks to the collecting habits and interests of her grandfather. Though she would first foray into the field of midwifery, Grace would eventually live with her husband, John Winter Crowfoot, in Egypt and, during the first world war, in Sudan. While her husband was then in charge of education and antiquities in the region, Grace spent time learning about and immersing herself in the lives of women in the community.

With these women, she learned how to spin and weave in the local tradition becoming a proficient weaver in her own right. She would later publish papers on the weaving methods she learned, which garnered the interest of the Egyptologists Hilda and Flinders Petrie. Crowfoot and the Petries worked together, with Crowfoot demonstrating that textile production methods of 19th century CE Sudan strikingly resembled those of 11th century BCE Egypt. Grace would continue to work on textiles from archaeological contexts and, together with other female archaeologists from Scandinavia, imparted on the field the importance of preserving fabric remnants for analyses. Her work helped in training future generations of textile archaeologists and her scientific pursuits would later inspire her own daughter, Dorothy Hodgkin, who would go on to win a Nobel Prize in chemistry.

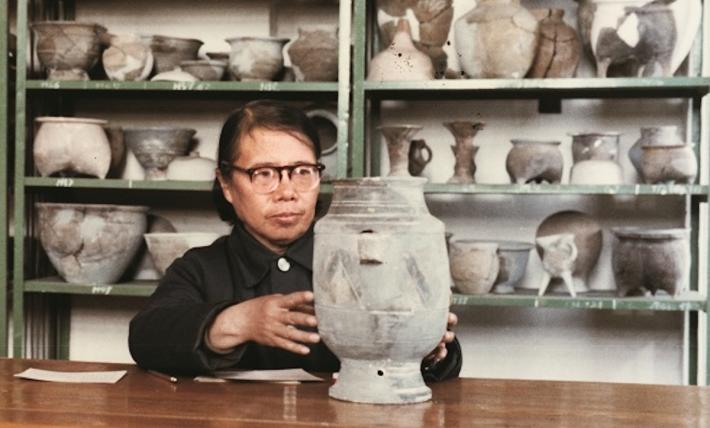

Zheng Zhenxiang (b. 1929) is a Chinese archaeologist whose work on Shang Dynasty (1600-1046 BCE) tombs has proved influential in the field to this day. Considered by some, the ‘First Lady of Chinese Archaeology’, Zheng is among the first generation of pioneering women archaeologists in China. When she entered the archaeology department at Peking University around 1950, she was the only woman among the students. Eventually graduating with a master's, she opted for active fieldwork over teaching positions and found employment at the Institute of Archaeology with the Chinese Academy of Sciences. She eventually became deputy head of the Anyang region’s archaeological team.

In 1976, Zheng organized an excavation in Yinxu on the site of a palace structure. Though the palace’s foundations seemed out of reach and many workers thought the digging should stop, Zheng’s insistence meant the team would eventually uncover one of the most important tombs ever discovered in Chinese archaeology. The tomb, which was discovered to belong to Fu Hao, a Shang Dynasty Queen, and General, was pristinely preserved and contained priceless objects and inscriptions which aided in furthering our understanding of Shang Dynasty life and burial practices.

Tatiana Proskouriakoff (1909-1985) was a Russian-born archaeologist whose contributions to the study of pre-Colombian Mayan culture greatly expanded our understanding of the Maya language and writing system. Tatiana moved to the US from Tomsk, Russia with her parents in 1916. She later enrolled in the College of Architecture at Pennsylvanian State University. She was the only woman in her graduating class of 1930. Even from the beginning of her career as a staff member at the Carnegie Institute, Tatiana revolutionized Mayan archaeology through the development of novel dating methods for monuments.

She worked for a time on the monuments of the Maya, utilizing her artistic skills to draw brilliant reconstructions of the ruins she studies. Her biggest contribution, however, has been considered her later work on Mayan hieroglyphs. Not only did her analyses settle debates regarding the cultural affiliations of sites like Takalik Abaj, but her breakthrough decipherment of the Mayan language has allowed for our greater understanding of Mayan culture and history through their historical records.

Harriet Ann Boyd (1871-1945) was an American archaeologist who helped stake a claim for women in ancient Mediterranean archaeology. Educated in Classics at Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts, Harriet pursued her studies further at the American School of Classical Studies in Athens (ASCSA) where she also spent time working as a volunteer nurse in Thessaly during the Greco-Turkish War. When she first requested to join archaeological excavations with ASCSA professors they discouraged her from engaging in fieldwork and instead suggested she become an academic librarian. Frustrated with their lack of support, Harriet took it upon herself to find excavation opportunities, looking to unexcavated areas on the island of Crete.

She made important discoveries during these early Cretan explorations but her later work discovering and recording the ancient settlement at Gournia (ca. 2800-1200 BCE), a prominent palatial site that served as a major trading hub, would constitute one of her greatest contributions to Bronze Age Mediterranean archaeology. Her continued work on Gournia and other sites on the island would lead her to become one of the foremost authorities of the Cretan Bronze Age during her time.

Danielle Vander Horst

Dani is a freelance artist, writer, and archaeologist. Her research specialty focuses on religion in the Roman Northwest, but she has formal training more broadly in Roman art, architecture, materiality, and history. Her other interests lie in archaeological theory and public education/reception of the ancient world. She holds multiple degrees in Classical Archaeology from the University of Rochester, Cornell University, and Duke University.