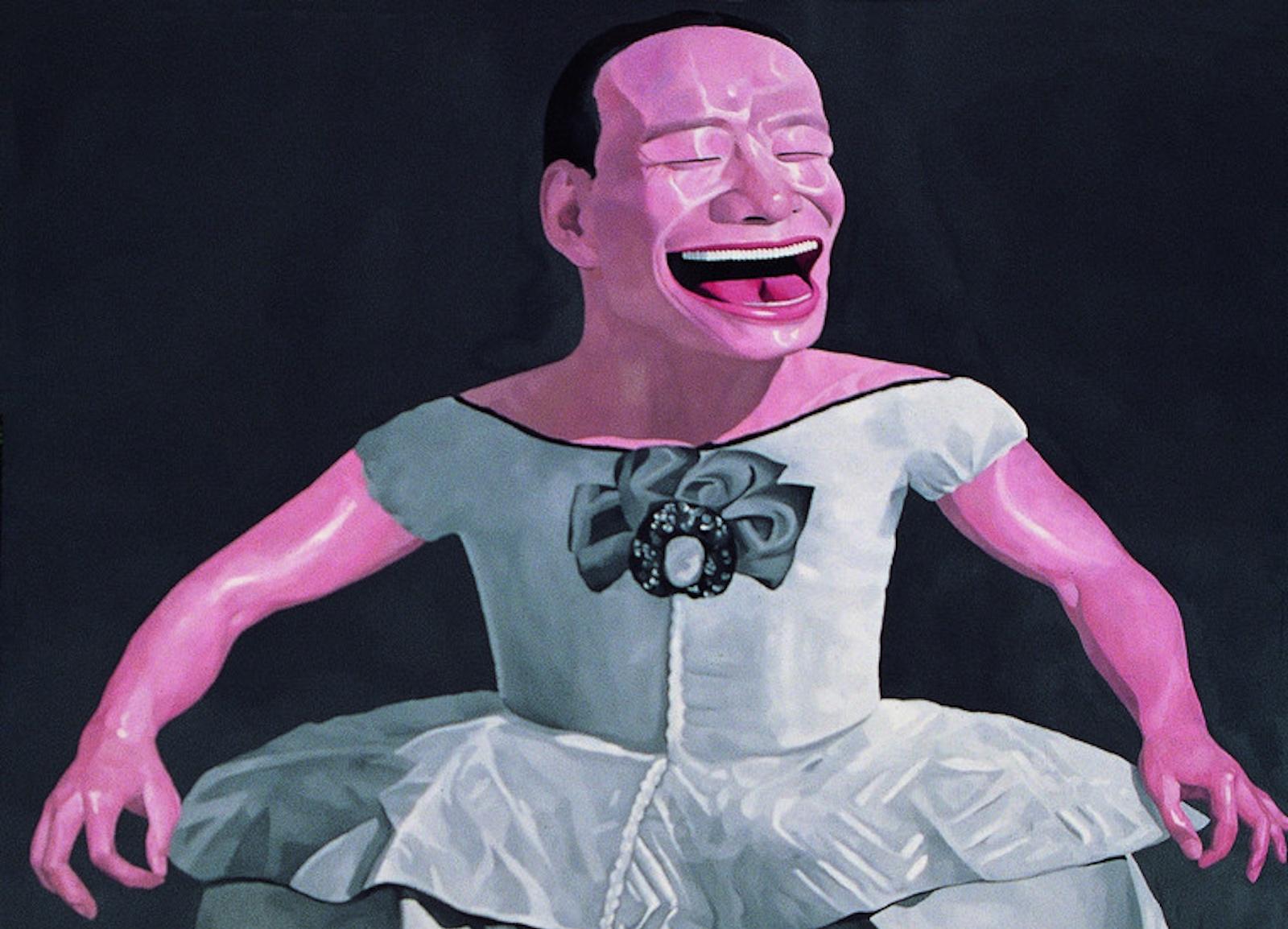

The first part of the exhibition is dedicated to the re-interpretation of famous Western art pieces by Chinese artists. A robed chimpanzee plays the role of Marat in Qiu Anxiong’s The Doubter, a clear reference to Jacques-Louis David’s Death of Marat (1793), while Yue Minjun replaces the central figure in Velázques’s Las Meninas (1656) with his famous self-portrait, a pink laughing man. These pieces reveal the impact that globalization had on the Chinese artistic environment. Although cultural exchanges always existed, the contemporary dialogue between the West and China has some specific characteristics.

Ferrell explains that: “After the end of the Cultural Revolution (1976), when Deng Xiaoping’s Open Door Policy was put in place, there was an inevitable flood of Western artistic material into China, and specifically into the freshly-re-opened art academies. [...] European and American exhibitions started traveling to China. The next few decades saw young Chinese artists take on and recreate pieces and styles from the Western art canon, begin to be featured in international exhibitions, and for a few, move abroad.”

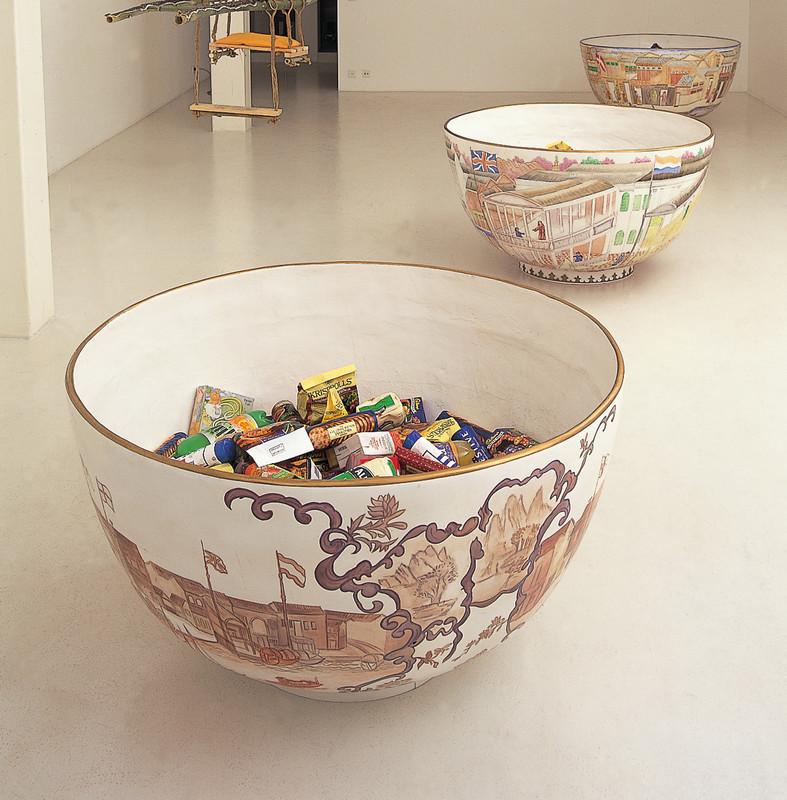

The second section explores advertising and the presence of Western brands in the Chinese market. With the end of the Cultural Revolution (1966-76) and the progressive opening up of China, Western brands such as Coca-Cola and Nike, began to be imported into the country and created a new wave of consumerism and brand-awareness. To explore this phenomenon, artists such as Huang Yong Ping (1954-2019) incorporated traditional Chinese aesthetics and symbolism with the language of Western art.

Huang’s Da Xian: The Doomsday consists of three large porcelain bowls decorated with the flags of the Western powers that colonized China in the nineteenth century. Inside the bowls, Huang placed British packaged foods that shared the same expiration date “Best Before 1 July, 1997,” the date of Hong Kong’s handover to China. While The Doomsday can be read as a critique of capitalism, consumerism, and colonization brought by Western powers, it can also be seen as a reminder that Chinese people have always been resilient. Life can be seen as a full bowl, even in adverse times.