Chen, born Chang Li Ying, in Nanxun, a town in the south-eastern province of Zhejiang, China, came from a privileged family. Her father was an antique art dealer who traveled between Paris, London, and New York. Although abroad, the family maintained a strong connection with their Chinese identity. They spoke Mandarin at home and frequently traveled to China. This privileged lifestyle, enriched by different cultures and languages, had a strong impact on Chen’s life. As a teenager, she moved to America to pursue her education and attended the Arts Students League of New York. In 1927, Chen returned to Paris and decided, despite her parents’ concerns, to become a full-time artist. Three years later, at the Chinese Consular Office in Paris, she married Eugene Chen, a lawyer and journalist with an active role in the Chinese political environment of the first half of the 1900s.

Georgette Chen, Family Portrait. Oil on canvas. Donated by Estate of Georgette Chen Liying.

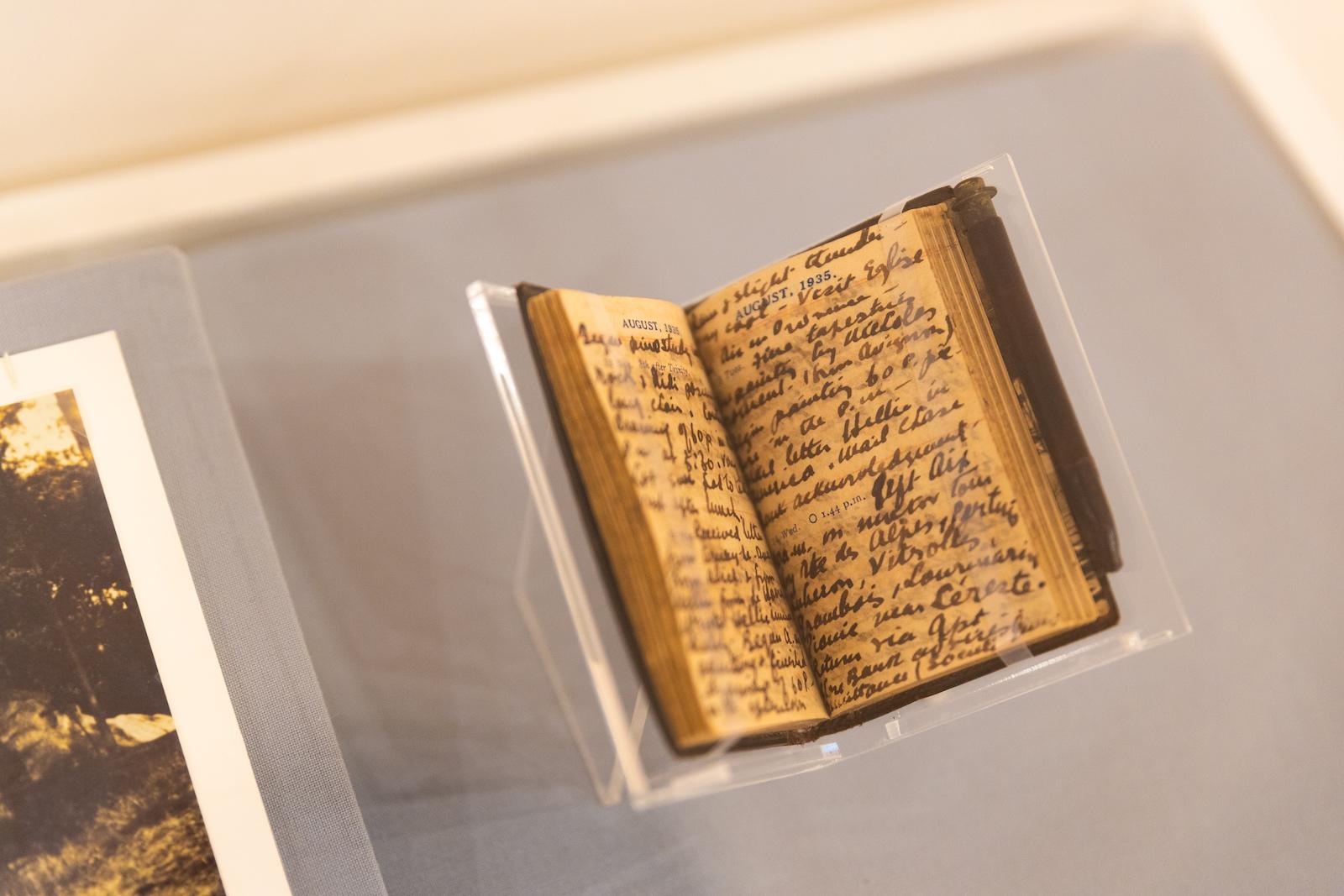

This year, the National Gallery Singapore celebrates one of the most fascinating artists of the twentieth-century—Georgette Chen. The exhibition Georgette Chen: At Home in the World presents Chen’s most significant works together with newly found archival materials, such as letters, diaries, and photographs. The first part of the exhibition is dedicated to Chen’s years in Malaya and Singapore, while the second part focuses on her early years, her training, and the international recognition she achieved during her life.

Installation View of Georgette Chen: At Home in the World.

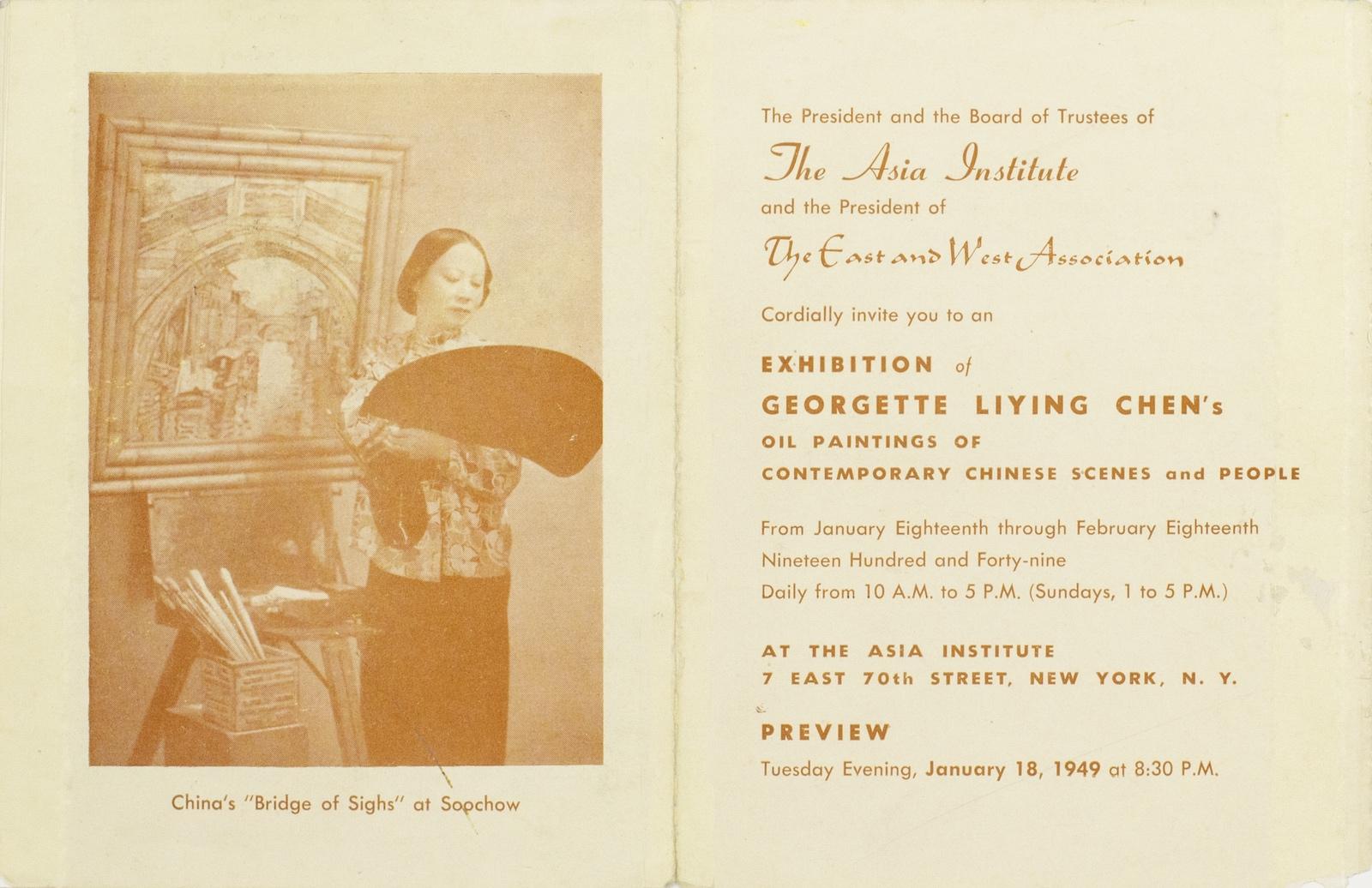

Detail of invitation card to Georgette Liying Chen’s Oil Paintings of Contemporary Chinese Scenes and People, 1949. Collection of National Gallery Singapore Library & Archive, gift of Lee Foundation.

For Chen’s artistic life, 1930 was the year that saw her debut as a professional. Two of her paintings, Nu and Vue Sur la Seine aux Andelys, were selected and presented at the Salone d’Automne in Paris. By the mid-1930s, Chen had become an established painter. Her first solo exhibition was held at the Galerie Barriero in 1936 and, along the years, her works were selected and acquired by some of the most important Parisian galleries and museums.

Georgette and her husband relocated to Hong Kong but were arrested when the city fell under Japanese control in 1941. Eugene’s political alliances were known—he was an anti-imperialist—and he had always refused to collaborate with the Japanese. Despite the turmoil brought by the war, Chen kept traveling around China and exhibiting her works. Many of her still lifes with gourds, baskets, and cultural Chinese elements, such as mooncakes, are of this period as it was safer for her to paint inside.

Georgette Chen. Vegetables and Claypot. c. 1940-1947. Oil on canvas, 73 x 60 cm. Collection of National Gallery Singapore.

After the death of Eugene in 1944, Chen remained in China for three more years and then returned to Europe. It was in 1953 that she decided to move permanently to Singapore where she became not only a well-known artist in the local scene but also a teacher and a mentor at the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts (NAFA). She described Singapore as “a veritable paradise [...] with all these motifs of the East to which I am dedicated. [...] Feeling immediately at home in this world where East meets West.”

Artistically, Chen belonged to the Nanyang art atyle, a movement that blended Western techniques—the use of colors and lines were those of post-Impressionism—with traditional Chinese ink and wash painting. The main representatives of the Nanyang style were those Chinese artists, part of the Chinese diaspora of the twentieth century, who had settled in Southeast Asia and were affiliated with the NAFA. The scholar Qilin Zeng notes how Chen was “one of the Chinese overseas painters who reflect their subtle identity changes and shifting sense of belonging in their artwork.” Dr Eugene Tan, director of the Gallery remarks “the impact she [Chen] has had on the development of visual arts in Singapore continues to influence generations of local artists.”

Pages from Georgette Chen’s 1935 diary. Collection of National Gallery Singapore. Library & Archive, gift of Lee Foundation.

Chen is arguably one of the most interesting artists of the twentieth-century, not only because her fascinating life seemed to follow major historical events, but because her art truly had no boundaries. She was Chinese by birth, French and American by education, and Singaporean by choice. Her paintings are a fusion of techniques, colors, and perspectives. She had chosen the name Chen as her signature. It was her husband’s surname, the man who always believed in her talents, and a clear reference to her chosen home, Singapore. “I now have a Malay name [...]” she wrote in 1963, “I chose Chendana (sandalwood). [...] to be a piece of wood is better since I am a natural blockhead. Now I remain one with a difference—a fragrant one!”