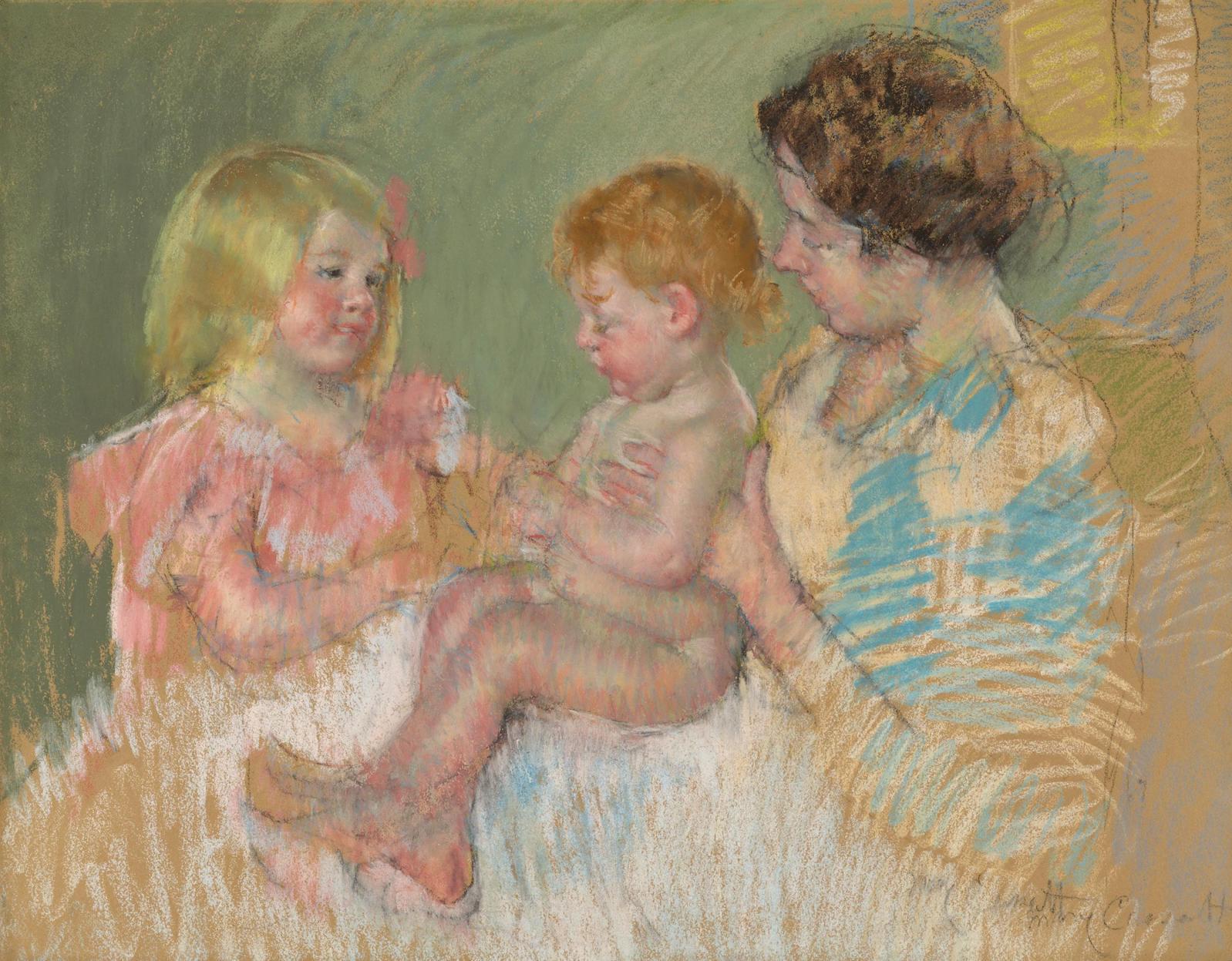

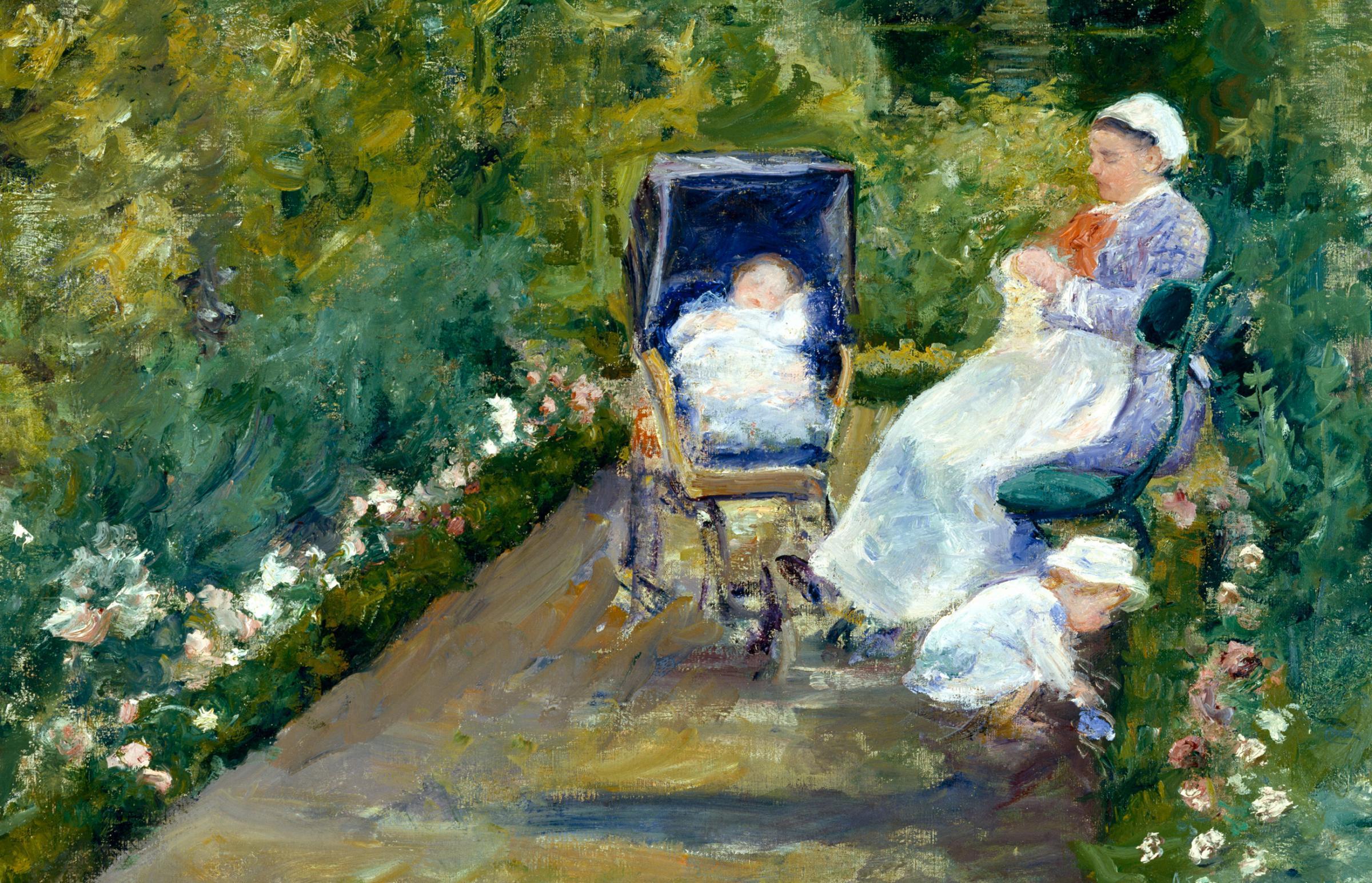

“The history of American painting is the history of French painting,” says the DAM’s curator emeritus, Timothy Standring, in our telephone interview. “If I sent people in without any labels, they would assume these are French paintings.”

Standring initially imagined the American Painters in France exhibit about ten years ago. With 113 works from 42 lenders, the exhibition shows at the DAM through March 13, 2022, then at Virginia Museum of Fine Art in Richmond from April 16 to July 21.

Heinrich says, “The Americans went to France to learn from their peers, the Academic painters as well as the Impressionist rulebreakers.” Thus, American artists of the era found in France a supportive arts culture not yet developed in the U.S.

“France had the infrastructure because of state support and an almost national pride of the French who equated art with the national reputation. In 1866, 11 to 14 million people went to the salon,” Standring explains. “The salon was like the Olympics for painting in the 19th century, the Super Bowl! To be juried in was a badge of honor.”