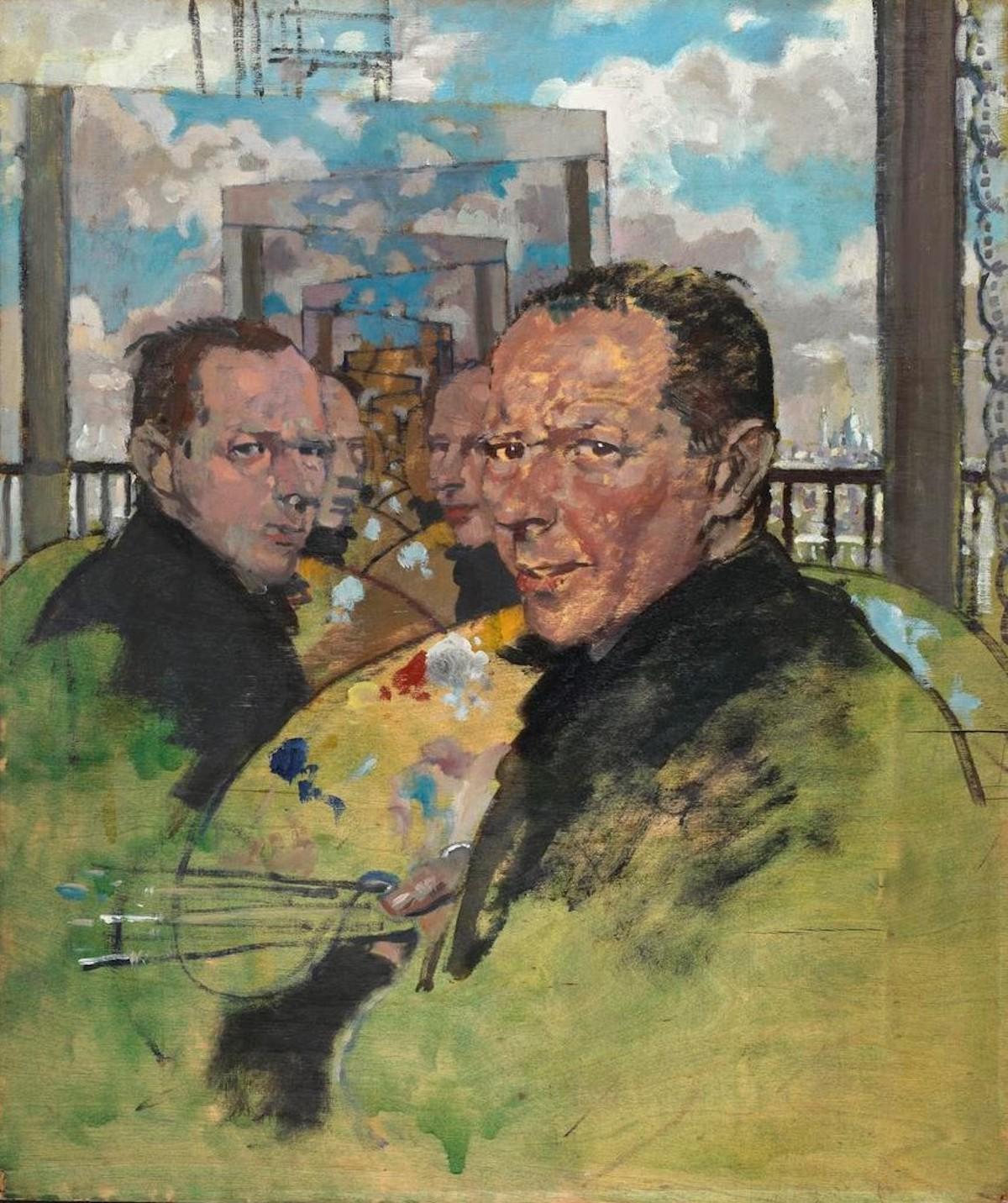

Professional success and personal turbulence colored Orpen’s early career; he ended his academic training with one of his most critically acclaimed works, The Play Scene from ‘Hamlet’ (1899), before graduating and painting The Mirror (1900), which established his thriving career as a swagger portraitist. Both pieces are overtly academic: Play Scene is based on Shakespearean scholarship, and The Mirror (starring his then-fiancée and model from Slade, Emily Scobel) uses a circular glass to reflect himself at his easel, per van Eyck’s example, and object placement per Whistler’s Mother. Though Orpen’s figure is absent from his most famous conversation piece, Homage to Manet (1909), it becomes a self-portrait by reiterating his obsession with reflection. The scene stages Irish novelist George Moore, as he reads art criticism to five of Orpen’s peers. Sitting at a table, they are beneath the watchful facsimile of Manet’s 1870 portrait of Eva Gonzalès, and all before the eye of Orpen himself.

These flamboyantly intertextual paintings affirmed Orpen’s artistic stature and prompted a catalogue of commissions. After opening a private school and studio in 1903, demand for Orpen’s society portraits swelled. He fetched enough to make himself one of the most commercially popular artists of his generation. This is a small wonder, considering the tangible legacy of Orpen’s influencers—Manet and Velázquez, to name a few—and his portraits’ intimacy. Ranging from self-images and domestic embraces in Night no. 2 (1907) to confrontational female gazes in The Angler (1912), and to Winston Churchill’s famed 1916 portrait, Orpen’s portraits are most notable for their reflection of individual identity.