As the rebellion unfolded, the Chinese government and the Qing Empress Cixi realized that the Boxer could be exploited to eradicate the economic, military, and territorial privileges that foreign powers had in China. Yet, the Chinese hopes were short-lived. A coalition of Western troops, well-equipped and technologically more advanced, soon managed to capture the capital. By 1901, the Chinese government was forced to surrender and accept a series of humiliating concessions.

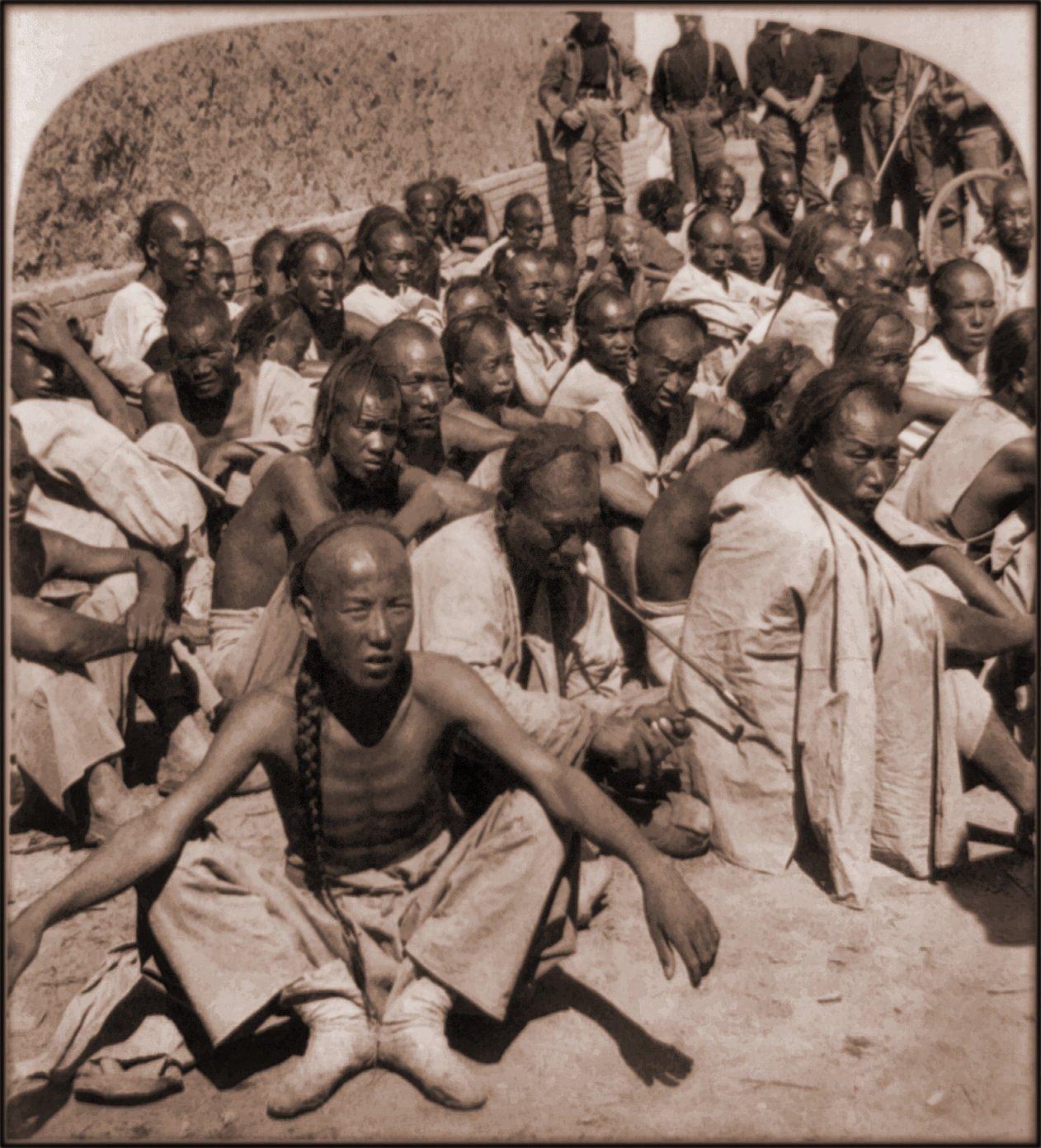

The images produced during the Boxer Rebellion capture the understanding Western powers had of China. Employed by Underwood & Underwood (New York) to make stereoscopic images of the Far East, the American photographer James Ricalton (1844-1929) arrived in China in 1900. His photographs show an array of underfed and weak unskilled laborers and soldiers, prisoners of war, and civilian casualties. His Some of China’s Trouble-makers: Boxer Prisoners Captured and Brought in by the 6th US Cavalry — Tientsin, China. No. 63 is arguably one of the most famous shots of the war.

In a caption, Ricalton explained that the men were obviously Boxers because one had been found with a weapon. He then claimed that “By far the larger part of the population of the empire is of this low, poor, coolie class. [...] Tomorrow they may be shot—but, whether it is bambooing, shooting, or beheading, one fellow decides he will have a smoke.”